In the annals of criminal history, certain cases stand out not just for the magnitude of the crimes involved, but also for the apparent actions of a state to cover them up and absolve the perpetrator. There can perhaps be no more disturbing example than the case of Dr. John Bodkin Adams. Adams was a man whose polite demeanor and status as a physician masked a sinister reality. Born on January 21, 1899, in Ireland, Adams would later become infamous as one of Britain’s most notorious suspected serial killers.

Adams’ journey into infamy began innocuously enough. He studied medicine at Trinity College Dublin, graduating in 1923. He then pursued a career in general practice, eventually settling in the English seaside town of Eastbourne. It was here that Adams would establish his practice and, unbeknown to the local townsfolk, embark on a dark path that would ultimately lead to suspicion of multiple murders.

At first glance, Adams seemed the epitome of a caring and dedicated doctor. He built a reputation for himself as a compassionate physician, particularly among the elderly population of Eastbourne. However, beneath this facade of benevolence lurked a much more sinister reality.

Adams’ modus operandi was as insidious as it was calculated. He would befriend wealthy, elderly patients, many of whom were were fit and well prior to his appearance. Once he had done so and their health had mysteriously begun to decline, he would coherce them into bequeathing substantial sums of money and valuable possessions to him in their wills. Each patient in fact was signing their own death warrant, as it was then only a matter of time before they would meet a premature death, usually through the administering of the powerful opiod painkiller morphine.

The true extent of Adams’ crimes may never be known. Many authorities attribute over 160 deaths to him, although some believe the actual number to be significantly higher.

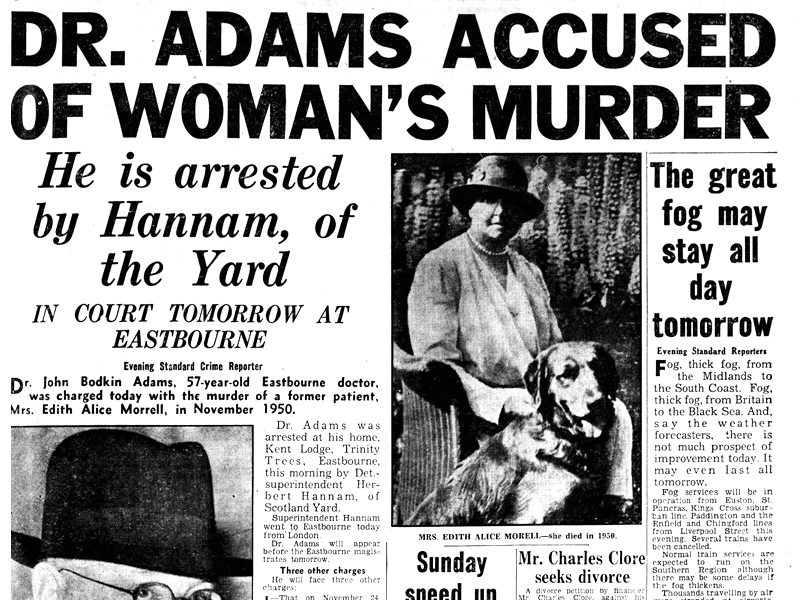

Despite years of local rumors about Adams’ conduct, it was only in the summer of 1956 that the authorities began to investigate. An anonymous tip-off about the suspicious death of elderly widow Gertrude Hullett while in Adams’ care provided the catalyst. Detective Superintendent Herbert Hannam of the Metropolitan Police was eventually assigned to lead the case.

In due course, Hannam’s inquiries brought him into contact with Annie Sharpe, the owner of a local boarding house where at least two of Adams’ victims were known to have met their deaths. After interviewing Sharpe, the detective concluded that she could become a prime witness for the prosecution. However, still a working doctor, Adams hastily diagnosed Sharpe with a terminal illness. Without consulting any other medical opinion, he prescribed her morphine and within a matter of days she was dead. Sharpe’s body was swiftly cremated. Serious questions must remain as to this day as to why the police did not intervene and initiate an autopsy and toxicology report?

Adams was initially arrested on 24 November of that year on lesser charges relating to his activities, namely the falsification of details on cremation certificates. While conducting a search of his home at the time, police caught the physician attempting to hide two bottles of morphine. When challenged by the detectives, he explained that one of them was for Annie Sharpe, the key witness who had died only days before. Adams was subsequently released on police bail.

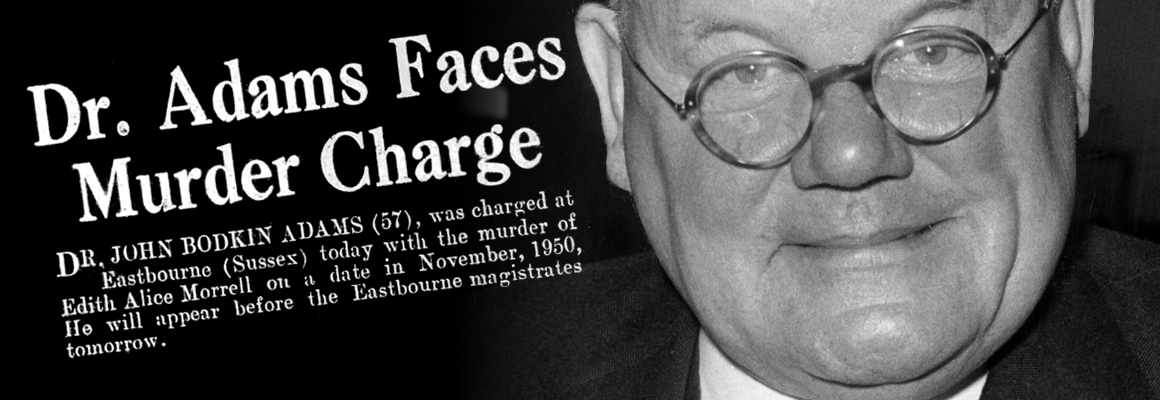

Finally, on 19 December, Adam’s was arrested and charged with the murder of one of his patients, Edith Alice Morrell. Reacting to the charges against him, Adams said…

“Murder… murder… Can you prove it was murder? … I didn’t think you could prove it was murder. She was dying in any case.”

By this time, Hannam had amassed evidence pertaining to at least four cases of murder. Alongside the name of Edith Alice Morrell went those of fellow elderly patients Clara Neil Miller, Julia Bradnum and Gertrude Hullett. The latter had left Adams her valuable Rolls-Royce Silver Dawn automobile in a will penned only five days before her death. The physician disposed of it for a large sum days before he was arrested.

The trial began at the Old Bailey in March 1957 and caused a sensation, drawing widespread media coverage and public interest from around the globe. Despite the gravity of the charges against him, Adams maintained his innocence throughout, presenting a calm and composed demeanor that belied the seriousness of the accusations. Perhaps he knew something that no one else in that courtroom did?

On April 9, the trial ended in controversey with Adams being acquitted. However, evidence subsequently came to light that pressure was exerted from the highest levels of both government and the medical profession to bring about that outcome. Many believed that the justice system had not only failed but had been perverted, and that Adams had escaped punishment for crimes far more extensive than those for which he stood trial. It came to light that the physicians association the General Medical Council (GMC) had written to all the local doctors in Eastbourne and cautioned them not to assist in the police investigation, citing the need to preserve patient confidentiality. Personal links were also uncovered between Adams and the prime minister of the day Harold Macmillan. Most telling of all, the police and court files were sealed by law for 75 years, thus preventing any public scrutiny.

By strange coincidence, just three weeks before the Adams verdict was announced, the British Parliament passed an act that narrowed the scope of capital punishment and would have spared him the hangman’s noose.

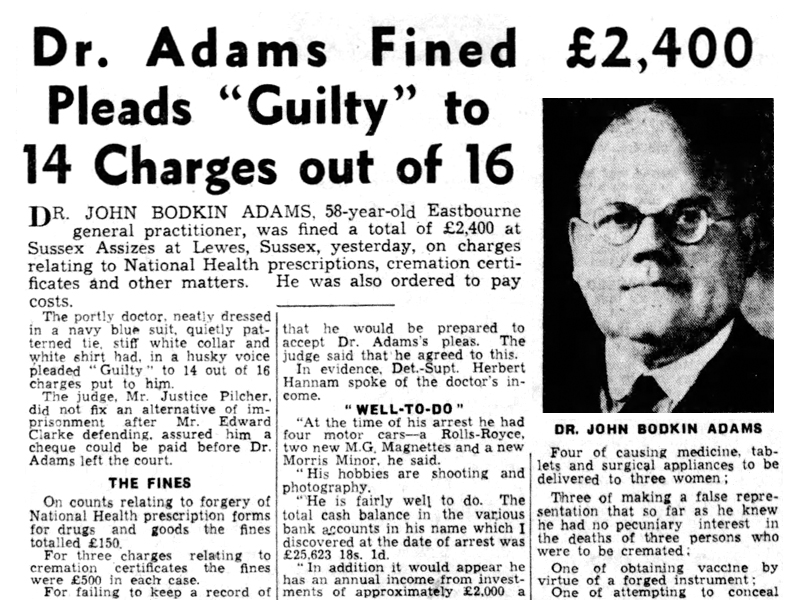

Finally, in November of that year, the General Medical Council revoked Adams’ medical licence. Alas, this was only in response to a subsequent trial in which Adams was accused of forging prescriptions and other acts of medical malpractice. This time he was found guilty and fined £2,400. Unimaginably, the General Medical Council chose to welcome Adams back into their ranks several years later.

In 1962, perhaps hoping to escape the suspicions that still hung over him, Adams applied for a visa to visit America. His application was refused.

In the years since Adams’ death in 1983, fascination with his case has endured, inspiring numerous books, articles, and even a television series. The question of his guilt remains a subject of debate among historians, criminologists, and amateur sleuths alike. However, when confronted with the facts it is hard not to conclude that Adams was indeed a merciless killer who preyed on the most vulnerable and only escaped justice due to the nature of his profession, and those who would go to any length to shield its reputation.

As a footnote, almost half a century would pass before another British physician would make similar headlines. His name was Dr. Harold Shipman.

EVENING STANDARD (1956)

DAILY MAIL (1957)